Written by Brady Dennis on June 22, 2015, via Washington Post. Click here to read original article.

Written by Brady Dennis on June 22, 2015, via Washington Post. Click here to read original article.

Researchers in North Carolina are developing a “smart” insulin patch that can automatically detect and manage blood sugar levels, an effort they hope might one day make painful, persistent insulin injections obsolete for millions of people with diabetes.

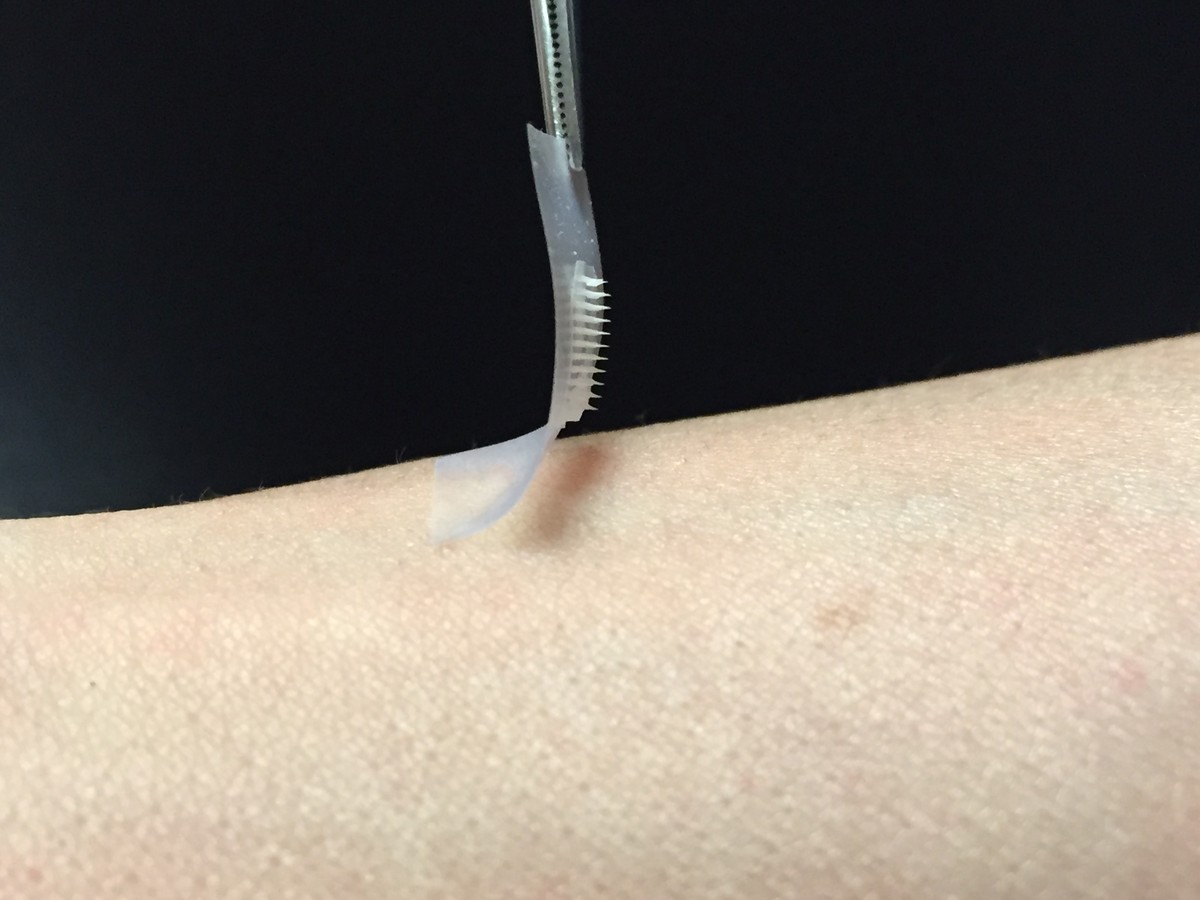

The patch is a thin square no larger than a penny. Its surface is covered in scores of “microneedles,” each about the size of an eyelash, which store both insulin and a glucose-sensing enzyme that can recognize increases in blood sugar. When that happens, the tiny needles can deliver the needed dose of insulin quickly and painlessly.

Researchers from a joint project at the University of North Carolina and North Carolina State University have tested the smart insulin patch only in mice so far. But the patch showed the ability to lower blood glucose levels in mice with Type 1 diabetes for up to nine hours, according to a study published Monday in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

“This is way cool technology,” said John Buse, a co-author of the paper and director of the UNC Diabetes Care Center. “It’s very, very exciting, but very preliminary. It will take years to work out whether this actually will work well in humans. But if it did, it would be amazing.”

Diabetes affects nearly 350 million people worldwide, according to the World Health Organization, and that number is expected to continue to climb. Nearly 30 million Americans suffer from the disease, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Managing blood sugar levels for many people with diabetes is a constant chore, marked by finger pricks, insulin shots and monitoring of the diet. Even then, keeping glucose levels in check is an imprecise science with serious consequences if a patient receives too much or too little of the hormone. In particular, patients with rarer Type 1 diabetes, in which the body doesn’t produce the insulin needed to convert sugars and other food into useful energy, have to maintain a consistent watch on blood sugar levels. But even patients with Type 2 diabetes can find it hard to give themselves the proper dose of insulin.

“The hard thing is to take care of diabetes day after day after day,” Buse said. “It’s somewhere in between a hassle and straight up pain in the butt.”

Advances in technology have helped make the task easier over time. Researchers have tried to cut back on the potential for human error by developing “closed-loop” systems that connect devices that monitor blood sugar and administer insulin. But even those products require regular attention; they have mechanical sensors and pumps that can malfunction and needle-tipped catheters that must be replaced.

The idea behind the “smart” insulin patch, is to eliminate some of those headaches while emulating the body’s natural insulin generators, known as beta cells, which sense increases in blood sugar and trigger a release of insulin. When the patch is placed on the skin, researchers said, the microneedles painlessly pierce the surface and tap into the blood flowing through the capillaries.

In early tests, the researchers found that diabetic mice given injections of insulin saw their blood sugar levels normalize but then climb back into hyperglycemic range relatively quickly. Mice that received the insulin patch, however, saw glucose levels come under control in a half hour and stay that way for several hours.

In addition, researchers said they discovered that they could fine tune the patch to alter blood sugar levels within a certain desired range. That offers hope that the patch might one day be tailored to each patient. They also hope to develop a patch that eventually could work several days at a time for human patients.

“The whole system can be personalized to account for a diabetic’s weight and sensitivity to insulin,” Zhen Gu, a professor in the Joint UNC/NC State Department of Biomedical Engineering, said in a statement about the study. “So we could make the smart patch even smarter.”

Monday’s study was funded in part by awards from the North Carolina Translational and Clinical Sciences Institute and the American Diabetes Association.